ArtSeen

Matvey Levenstein

New York

Paul KasminJanuary 24; March 2, 2019

There are fifteen oils on wood, canvas, or copper, and six large Sumi ink drawings on paper in Matvey Levenstein's first solo show in New York since his exhibition at the now-closed Larissa Goldston Gallery in 2009. Dating from 2015 to 2018, the works address traditional genres of landscape, still life, and portraiture, but Levenstein has developed a process that combines art historicism, casual photography, and technical rigor via a realistic perfectionism that both guides you into the artist's own world and lends magnitude to the quotidian. The pictures do not resemble those of Vermeer, but these explorations of settings of subtle historical significance on Long Island's North Fork around Orient, New York, elicit a similar level of truth.

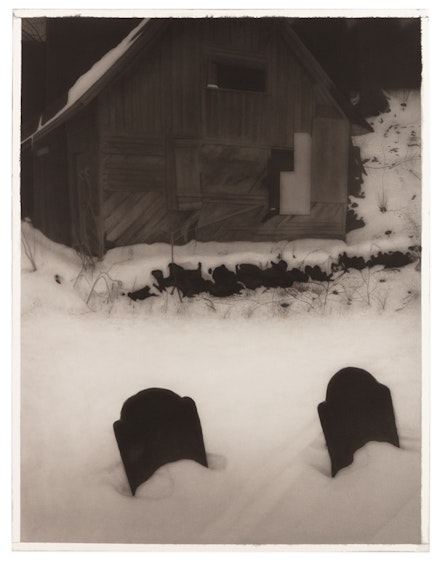

Starting with iPhone photos, some dating back to 2009, Levenstein employs a conceptual process of selecting and expanding or shrinking images without the aid of a projector. It is a manual translation of the intimacy of the phone screen, first to drawings and then to oils. In some cases, such as the large scale and monochromatic Snow 2 (2016), with its dense blacks, the drawings end up being more vivid than the slightly chromatic smaller paintings such as Snow (2018), which bear the silvery and shimmering qualities of delicate daguerreotypes or early Gustave Le Gray albumen prints. There is a symbolist seductiveness to Levenstein's landscapes and still lifes, a psychological freight conveyed via weather and mood constructed of legible but irresolute forms, accomplished without facture. They bear a lingering trace of the Sumi ink grisaille works and Hammershøi-like interiors he did on paper in the mid-1990s after spending a few years working as a sculptor. Those were a distillation of the softened modern sfumato of Seurat and Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer made with a technical rigor and control that recalled the art of one of his professors at Yale, Vija Celmins. This method was followed by a period of works that were more dependent on color as tone, but in the new material he has whittled it all down to gently modulated hues in an increasingly limited range on surfaces near absent of visible brushwork. The muted colors in the oils give them the quality of faded images in mid-century magazines, such as LIFE or Look, seemingly grafting onto them an inherent nostalgia, one that dovetails with the title of works such as Pilgrims (2018), a reference to early settlers' graves in Orient and human passage.

But Levenstein's figurative and landscape work, as he noted in an interview in 2009, is not about the past. It fulfills his dictum that "by moving backward you in fact can step ahead." This is a critical notion in the newly expanded idea of the post-French avant-garde, from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Symbolists and through to 20th century artists such as Stanley Spencer, Salvador Dalí, Christian Schad, Dorothea Tanning, Jared French, Peter Blume, Leonora Carrington, or Laura Wheeler Waring—an alternative history of art still in evolution. As the rethinking of criteria of value in modern and contemporary art has finally come to embrace the persistent figurative and realist traditions, committed work such as Levenstein's demands critical attention, and rewards close looking.1

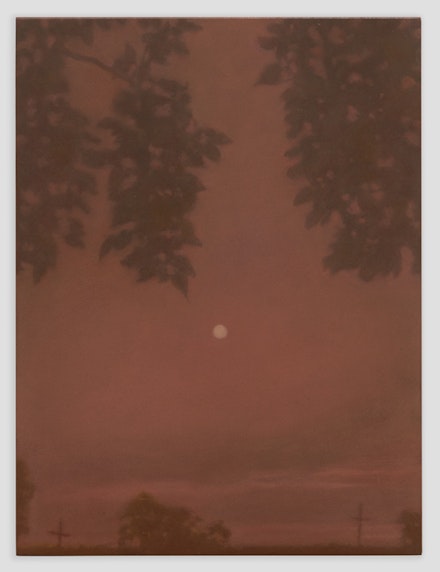

The range of pop, cinematic, and art historical references are impressive and effectively calibrated to be oblique. Pink Moon (2018) calls to mind musician Nick Drake and the similarly dulcet harmonies in Caspar David Friedrich's work, absent an intrusive Rückenfigur. But such figures of identification from German Romanticism do appear in Levenstein's still lifes, in the forms of cut flowers arranged in drinking glasses, sunflowers in an unassuming vase, an effusive bouquet in a reflective earthenware jug worthy of Luis Meléndez or Velázquez. Flora sit near the center of compositions as stand-ins for figures or, when rendered monumental, as bust-length portraits. Such pictures fulfill what Levenstein calls a "condition of possibility." The use of casual photography to distance his conceptions from reality, to organize artificially a setting as a template for action in what he has referred to as a "theatrical situation," involves autonomous subjects, such as nosegays, or even the natural setting itself, awaiting a story. Levenstein's compact oils are also in a surprising dialogue with those of his wife, and fellow Yale alum, Lisa Yuskavage, seen here in two portraits, and whose six small pure and atmospheric landscapes were among the great and pleasant surprises in her "Barbie Brood: Small Paintings 1985-2018" show at David Zwirner in late 2018. Levenstein's seamless surfaces are in contradistinction to her marked facture, but both approaches advance the landscape genre.

A frustrated John Constable famously wrote of J.M.W. Turner's art that "he seems to paint with tinted steam, so evanescent and so airy." Levenstein similarly presents himself as a master of atmospherics, though they be demure in mood, as in works such as Gardiners Bay (2018), Sunflowers (2018), and Storm (2017), where sublime and sensate skies belie the pictures' small size (one foot high or wide). It is remarkable that by comparison the huge On the Beach (2018), at just over three feet high, bears the same visual punch as its smaller cousin Gardiners Bay, hanging cattycorner. The artist works with more subtlety than his other more Turnerian teacher at Yale, Jake Berthot, but there is a similar attempt to capture a motive quality of light and indeed air, though in a more painstaking form. At the same time, Levenstein's East End environs that date back to the mid-17th century when Vermeer was painting, have occasioned images that offer hard-won, often moving, feelings of permanence tinged with vanitas. Snowy images of Brown's Hill Burying Ground in Orient2 have become a mini obsession—he has employed the composition at least five times in his work since 2012, sometimes with slight tweaks of the deteriorating barn in the background. An historical marker at the site reads that it is a place where "the present meets up closely with the distant past," a fitting description of Levenstein's compelling, enduring, and quietly momentous concretization of perception.

Notes

- All quotes herein are from an interview by Phong Bui in The Brooklyn Rail, April 9, 2009.

- It dates back to the mid-17th century and is also known as Terry Hill Cemetery.